By Dr. B. Sultan:

Lady Macbeth once remarked that “a little water clears us of this deed” after the assassination of the King. Yet, with time, she remained haunted, obsessively rubbing her hands in an attempt to cleanse the imagined stains of blood. The persistence of narcotics production and trade in South-West Asia resembles this unending struggle — a dark reality that cannot be easily washed away.

Afghanistan has long been recognized as the world’s largest producer of opium, with its roots tracing back to the early 1900s. Over the decades, the repercussions of this industry spilled into neighboring Pakistan and Iran. In the late 2000s, Taliban leader Mullah Omar imposed a strict ban on poppy cultivation through threats, forced eradication, and severe punishments. However, as revealed by the UNODC Opium Survey 2007, the ban primarily targeted cultivation while the trade continued. After the fall of the Taliban, opium again became a major source of funding for logistics, weapons, and militia payments.

In 2022, the Taliban leadership once again announced a ban on poppy cultivation, with Hibatullah Akhundzada officially declaring significant reductions. Some Western reports, supported by satellite imagery, showcased declining poppy fields in southern Afghanistan. However, this raises critical questions: Can Afghanistan realistically abandon such a central economic resource while facing sanctions? And what consequences does this shift have for Pakistan?

While certain international outlets hastily claim that Pakistan has become a new hub for narcotics, such narratives ignore key realities. The issue is not a simple matter of “shifting sands” but a complex regional security challenge. The porous border between Pakistan and Afghanistan, coupled with cross-border networks of drug traffickers, means temporary shifts in cultivation are often strategic rather than permanent. Moreover, Afghanistan’s pivot towards methamphetamine production — highlighted by satellite evidence of expanded ephedra processing hubs — reflects adaptive strategies of traffickers rather than genuine eradication.

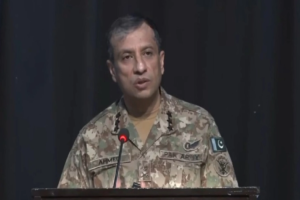

In Pakistan, however, the situation is markedly different. Since 2001, the country has largely maintained its “poppy-free” status, despite sporadic spillovers from Afghanistan. Following the Taliban’s 2022 ban, some illicit cultivations did emerge in border areas, particularly within Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Yet, these were swiftly addressed through Pakistan’s Poppy Elimination Campaign (PEC-2025). This multi-agency effort, led by the Anti-Narcotics Force (ANF) and provincial administrations, successfully destroyed thousands of acres of illegal poppy fields. Over 250 FIRs were registered, dozens of arrests were made, and awareness campaigns were launched across educational institutions. Importantly, independent surveys after March 2025 confirmed the effectiveness of these eradication drives.

Pakistan’s determination to combat narcotics often remains under-reported internationally, overshadowed by outdated or selective portrayals. The fact remains: Pakistan continues to fight this menace not only for its own stability but also for global security. What is urgently needed is greater recognition of these efforts by the international community and enhanced cooperation from agencies such as the UNODC.

As South-West Asia remains at the heart of global narcotics trade routes, Pakistan’s role is both frontline and decisive. Balochistan, in particular, holds the potential to transform from a vulnerable transit zone into a hub of opportunity, stability, and resilience. Just as Lady Macbeth’s imagined guilt could not be washed away with water, the global community cannot absolve itself of responsibility by ignoring Pakistan’s sacrifices and achievements in this ongoing struggle. The fight against narcotics requires collective recognition, support, and action — not selective narratives.